Churches at Kilcorney and Jordanstown

It is believed locally that the site on which Jordanstown Church is built is close to an ancient religious site dating back to the time of St. Patrick. The present church is situated in Kilcorney, which has been translated as Cill Catharnaigh meaning Catharnach’s Church.1 Information about St. Catharnach, who lived in the fifth century and is venerated on May 16, is unclear; there are various ways of spelling his name – Cairnech, Cairnigh, Carantoc and Carantech – and there are various opinions as to his birthplace. Cairnech means the Cornishman and some say that he was the son of a British chieftain in Cornwall but others believe that he came from Wales.2 It is said that he followed St. Patrick to Ireland and he is best known for his involvement in the compilation of the Senchus Mór, or as it is otherwise known Chronicon Magnum, which amended the Brehon Laws.[3] Under the direction of St. Patrick, he joined with eight others to form a commission comprising three kings, three bishops and three sages to legally rewrite the laws of Ireland, replacing the pagan aspects with Christian principles.[4] It is believed that Catharnach founded a church at Kilcorney and it is thought that Kilcorney Glebe is even older than the ancient glebe at Rathcore.[5]

The presence of a more modern church at Jordanstown can be traced back as far as 1787.[6] It is not known when this church was built, but on September 2, 1787, the Bishop of Meath, Dr. Patrick Plunket visited it and confirmed fifty-four children.[7] When writing about this period in the 1930s, the diocesan historian Dean Anthony Cogan commented that when Dr. Plunket commenced his visitations of each parish in his diocese in 1780:

the chapels were almost without exception, wretched, miserable, mud-wall, thatched hovels, unfit to shelter the beasts of the fields.[8]

It is quite probable that this description fitted the church at Jordanstown. Some attempt must have been made to improve it, as Dr. Plunket recorded in his diary when visiting Rathmullian (Rathmolyon) to administer the Sacrament of Confirmation in 1788, that there were two chapels repaired in the parish.[9] One of these would have been at Kill and the other would have been the one at Jordanstown.

The historian Fr. John Brady has interpreted William Larkin’s map of 1812 as showing a large L-shaped church at Jordanstown.[10] Fr. Brady claimed that this church was situated a short distance from the present church and was on the Ryndville Estate in Jordanstown.[11] This is most likely the church visited by Dr. Plunkett. Local folklore suggests that this was a thatched church and that it was burned around 1812.

Some local people believe that the present Church of Our Lady of the Assumption at Jordanstown was built in 1829. This may be correct or it may be an estimate of the year of construction, as the building of many churches commenced in that year, due to restrictions against Catholics being eased as a result of the granting of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. There was, however, an opinion that Jordanstown Church was built in pre-Emancipation times.[12] The site originally formed part of the estate of Lord Decies, who leased it to Cliffords and it is believed that when it later came into the ownership of the Clifford family, it was given free of charge to the Church.[13]

An article in the Freeman’s Journal newspaper of October 26, 1832 gives details of a donation towards the building of the church. The article appears under the heading Protestant Liberality and states:

Rev. Mr. Flood, R.C.C., Rathmolyon, gratefully acknowledges to have received from Robert Fleetwood Rynd of Ryndville Esq. the sum of twenty pounds towards the building of the chapel at Jordanstown.[14]

(interestingly, there is no record of a Fr. Flood serving in the parish at that time: Fr. John Flood, C.C. did not arrive until 1868). The donation of £20 would represent about €1,600 in today’s terms.[15] It was given at a time when an agricultural labourer’s weekly wage would have been about five shillings per week in summer and somewhat less than that in winter, when work was not as plentiful.[16] It would have represented about two year’s wages for such a worker. The donation from Mr. Rynd, who was a Protestant, was obviously viewed as being sufficiently noteworthy to make it a news item in a national newspaper.

At that time, the parish of Rathcore was no different to many other areas, where there was a difficulty in collecting tithes – a levy imposed upon all landholders, no matter how small their holding, for the support of the clergy of the Established (Protestant) Church. It was bitterly resented by Roman Catholics and widespread opposition to paying tithes resulted in the Tithe War of 1831. The paying of these tithes to the Protestant Rector of Rathcore, Rev. Richard Ryan appears to have ceased around then. In July 1832, he complained to the British authorities in Ireland that his circumstances had worsened to such an extent, that he was unable to educate his children or pay his workers, as he was no longer in receipt of this income.[17] Under these local circumstances, Mr. Rynd’s donation would have been an indication of his generosity and religious tolerance.

Although the newspaper article indicated that the donation was towards the building of the chapel, it is not clear whether it was used towards building a new church in 1832 or paying off a debt on a church built some years earlier or towards the repair of an earlier church. In any event, it is likely that Jordanstown Church was a low building as, notwithstanding the granting of Catholic Emancipation, a number of restrictions against Catholics remained and one of these meant that that no Catholic church could have a bell or steeple.[18]

By 1837, Jordanstown Church was undoubtedly in existence. It appears on the Ordnance Survey map of that year and the Lewis Topographical Dictionary published in the same year gives the following description:

The chapel is a spacious and handsome edifice, situated at Kilcorney, on the estate of Lord Decies.[19]

Even though the church was built at Kilcorney, it was known as Jordanstown Church . The parish was known as Rathcore and a silver chalice, which is still in the parish, bears this out. There are two inscriptions on it: 1799 and Rathcore 1855.

In 1862, Fr. John Masterson, P.P. had the church repaired and decorated.[20] It is possible that it was at this stage that a new altar was erected and the old one placed in the adjoining graveyard. Incorporated in the new altar, above the tabernacle, was a Gothic-type spire structure, which housed a crucifix. The spire was removed during renovations in later years. In 1876, a wooden belfry was erected to the north of the church and Fr. Michael O’Keeffe, C.C. blessed the bell when it was being hung there.[21]

There is some uncertainty as to when some of the stained glass windows in the church were installed and this will be explored later in the article but it appears that when Fr. Masterson died in 1878, his parishioners donated money for the installation of a stained glass window to his memory. It is of French origin and is an ornate window depicting the Assumption of Our Lady into Heaven, to whom the church is dedicated. The inscription beneath it reads:

Of your charity pray for the soul of The Very Rev. John Masterson P.P.V.F. who died Nov. 17 1878. To whose memory this window is erected by the faithful parishioners of Jordanstown. R.I.P.

It would appear that whilst he was parish priest, Fr. Hugh Behan installed another ornate window, to the memory of his family. It depicts the Sacred Heart and the inscription reads:

Pray for the souls of the Parents, Brothers and Sisters of the Revd. Hugh Behan P.P. Anno 1882.

In the following year, it seems that two parishioners subscribed towards the installation of two more stained glass windows in the sanctuary. Beside the window of the Sacred Heart is one of the Mother and Child and it is inscribed:

Pray for the parents, brother and sister of the donor of this window Edward O’Brien, Ballinaskea. 1883.

Opposite this window is one of St. Joseph, with the following inscription:

Pray for the parents of Patrick James Kennedy of Rathcore, the donor of this window 1883.

These windows still grace the church today.

A chalice was bought or donated in 1883. It is inscribed:

Jordanstown Church, Enfield. 1883.

In 1886, P.J. Kennedy donated a monstrance and the inscription reads:

The gift of Patrick James Kennedy of Rathcore to the Parish Church of Jordanstown. Nov. 1886. Pray for him.

The year 1891 marked the beginning of a period of bitter dissention between the Catholic clergy and the people of Ireland (this is outlined in detail in Chapter 49: The South Meath Election Petition). The three priests in the parish at the time, Fr. Patrick Cantwell, P.P. and curates Fr. William Rooney and Fr. Richard McDonnell were all politically active.[22] All three were anti-Parnell, whilst the majority of their parishioners held opposing views. In 1893, the holding of a Station Mass in some houses in the parish was apparently cancelled and this provoked an outburst, with political connotations, in a local newspaper:

Ten of the leading Parnellites of the parish of Kill and Jordanstown have been visited with a new and extraordinary form of boy-cotting. The usual stations were not held in their houses this Easter. If this be intentional it has the merit of cutting both ways, and may be felt more keenly by its authors than by its victims. To the ten Parnellites it means a saving of something like £20 a year, not to speak of the value of grass unconsumed by the parochial bullocks. And they know moreover that they can have a good many masses offered up for their intentions for less than they have to pay for one, by the best of good priests, who will not venture to catechise on their politics.[23]

Some of these ten may have been members of the local branch of the National League, which fought for the rights of tenant farmers and for land reform laws, and was pro-Parnellite in ethos. In August 1893, they voiced their intense dissatisfaction with a vote in the House of Commons. They criticised the Irish members of Parliament and attributed some of the blame for the election of two of the members involved in the vote, on the Meath clergy. At a meeting attended by local men including Edward O’Brien, Michael Healy, James Grevil, Patrick Bailey, James Deering, James Hope, Pat Gorman, John Ash and James Connell, they unanimously passed a resolution criticising the Irish members of Parliament and castigating the clergy saying:

That we, the members of this branch, enter our solemn protest against the cowardly conduct of the Irish Whigs in voting away twenty three seats in the English House of Commons before the land and other important questions are settled; and we are anxious to know what the Meath clergy have to say for themselves now and for their two darling members – Mr. Jeremiah Jordan and James Gibney. They would have acted more patriotically in leaving one to attend to his society – the Good Templers – and the other to take care of the man in the moon.[24]

In August 1893, the people of Jordanstown were informed that in future there would be only one Mass on Sundays and again, opinion was publicly expressed, with political undertones, in the local press:

Surely it cannot be that the priests are overworked: I should say that they are very much the reverse, else they would not have so much time to devote to propagation of bad Whig politics. The worthy curate of this same parish, Father McDonnell, was able to devote hours of time on several days of the past two weeks to ear-marking Parnellite voters to get them put off the register, and making claims for every Whig “gather-‘em-up” in the parish.[25]

The terrible animosity between clergy and parishioners gradually abated and eventually fizzled out. See also Chapter 34: Deaths, Funerals and Burials.

In 1901, John Cosgrove, who died in that year, left £100 in his will for the erection of new altar rails in Jordanstown chapel.[26] The marble rails arrived by train to Enfield railway station, where they were collected and brought by horse and cart to the church. Because of their weight, extra horses were required to get the cart up Clifford’s Hill at Kilcorney (between Bailey’s and O’Gorman’s). A plaque with the following inscription was erected in the church:

Pray for John Cosgrove, Rathrone, Donor of this Altar Rails. Died March 20th 1901.

A strip of red carpet used on the kneeling area of the altar rails, was hand-made by Mrs. O’Brien, Ballinaskea.

The remains of three parish priests were buried before the high altar in the church. They were Fr. Robert Tuite in 1842, Fr. Richard Ennis in 1854 and Fr. John Masterson in 1878. Another parish priest, Fr. Hugh McEntee was buried in 1906 in the church grounds to the northeast of the church.

On Sunday, December 30, 1906, a fund-raising concert was held in Jordanstown Church. Fr. Thomas Gilsenan, P.P. was one of the principal organisers and the money raised was used to buy instruments for Enfield Brass Band and to defray the expenses of the bandleader and a dancing teacher. The children of Baconstown National School played a leading role in the concert, with the senior boys dancing an eight-hand reel and other pupils singing in harmony. A comedy play Handy Andy was performed and the programme also included a pianoforte selection by Kathleen Brogan, Trim, the song Rory O’Moore by Patrick Hudson and renditions by K. Cosgrave, K. Hudson, Miss Clancy and Thomas McLaughlin. The concert was considered a very worthy event and there was an excellent attendance in the church, despite inclement weather and the fact that the roads were almost impassable.[27]

When Fr. Gilsenan came to Enfield in 1906, he found Jordanstown Church in a dilapidated condition and in urgent need of repair. The ceiling was in a crumbling state and the roof sagged in such a way that it was in danger of falling in at any moment.[28] On St. Patrick’s Day, 1907, he issued an appeal to his parishioners for the funds needed for renovation. It was expected that they would contribute about £500, but they gave twice that amount. Contributions also came from other priests and from friends outside the parish. The national schoolteachers of the surrounding parishes ran a raffle to raise funds.[29] A noted architect, Thomas McNamara, 50 Dawson St., Dublin, drew up plans.[30] The church was re-opened on St. Patrick’s Day, 1908 and an article in the Irish Builder and Engineer publication gave the following account:

The church, which is practically re-built, is of a most graceful design and reflects considerable credit on the architect, Mr. McNamara, of Dublin. The designs of the architect were entrusted to a well-known Dublin builder, Mr. Hanway, of North Great Georges Street and in the hands of that contractor the structural alterations were carried out in a manner that has evoked the admiration of all.[31]

The walls of the church were raised and a new roof put on. A chancel arch was erected, the interior of the church was decorated, some new pews were provided and old ones were renovated.[32] An article in a local newspaper at the time suggested that a stained glass window of the Sacred Heart was installed during the renovation period and historian Fr. John Brady also suggested that stained glass windows were fitted in 1908.[33] However, expert opinion on stained glass windows advocates that the four windows surrounding the sanctuary were fitted prior to 1900 and were most likely installed in the years indicated by the dates beneath the windows.[34] The stained glass expert contends that it is most likely that the church was originally fitted with sliding sash windows, which would have rotted over a period of time. As funds became available or as donors came forward, these windows would have been replaced with stained glass and leaded windows, even if the church was in a state of disrepair.[35] Notwithstanding the fact that the fabric of the church was in poor repair in 1906, the windows could have been in good condition and it may be that for the re-opening of the church in 1908, one window was re-installed and gave the newspaper reporter the impression that it was a new window.

The church was thronged for the re-opening ceremony, at which Solemn High Mass was celebrated. A choir under the direction of Mrs. Conway (a teacher in Longwood National School) sang at the Mass. Professor Peter Coffey of Maynooth College and a native of the parish of Enfield, acted as master of ceremonies and Fr. J.J. Poland, C.C., Mullingar, delivered the sermon.[36] He was presumably invited to fill this role as he had a reputation as an eloquent preacher and an entertaining speaker. Fr. Poland congratulated the priests and people of the parish upon the renovation of their church, which, he said would stand for years to come as a memorial of their faith and generosity.

Fr. Gilsenan addressed the congregation and congratulated his parishioners on the sacrifices they had made for their parish church. He said that they were a generous and noble-hearted people and that:

the priests and people of Jordanstown had very good reason to feel joyous and grateful that day. St. Patrick’s Day, 1908, should be a memorable day in the annals of their parish. Their beautiful church, as it now stood, reflected upon their generosity and also upon the architect and the contractor.[37]

From 1908 to 1910, three holy water fonts were placed in the church. They were inscribed:

- Pray for the souls of Very Rev. Hugh Behan, Very Rev. Patrick Cantwell, Very Rev. Hugh McEntee. 1908

A further inscription was later added: Very Rev. T. Gilsenan, P.P. 1906 – 1926

- Pray for the soul of Mrs. Mary Anne Mahon (Enfield) and the souls of her deceased relatives and friends. R.I.P. 1910

- Pray for the soul of Christopher Murray (Ballinaskea) and the souls of his deceased relatives and friends. R.I.P. 1910

In 1911, Jane Griffin, Ballinderrin, donated money for the installation of a triple-arch stained glass window, to the memory of her uncle. It is a crucifixion scene and its position behind the main altar affords it a focal point in the church. It was made in Munich, Germany, by Meyer & Co., a leading studio for stained glass and mosaic and is inscribed:

Pray for the soul of Peter Greville and the souls of his deceased relatives. R.I.P. 1911.

Surrounding the gallery are four simple stained glass windows and at the back of the gallery is a rose window depicting the Sacred Heart and symbols of the Passion. This window is probably the work of the Earley Studios, Camden Street, Dublin.[38]

Above the tabernacle on the altar in the church, is a sculptured piece of marble depicting a pelican feeding her young with the blood from her breast. The symbolism of the pelican is based on an ancient legend, which preceded Christianity. One version was that in times of famine, the mother pelican fed her young with her blood to keep them alive, but in the process lost her own life. Early Christians adapted this legend to symbolise Jesus Christ, who through His passion and death, gave His life for the redemption of mankind.

In April 1912, Henry Clifford (a member of the Church of Ireland) donated an area of land measuring one acre, three roods and sixteen perches for use as a graveyard behind Jordanstown Church. The Bishop of Meath and a number of priests of the diocese including Fr. Gilsenan were first registered as owners of the land on March 27, 1915. On October 22, 1959, it was registered in the name of St. Finian’s Diocesan Trust.[39] The graveyard was blessed in June 1928. In exchange for the land, the Church was obliged to build a roadside wall on Mr. Clifford’s other land opposite the church. The builders left a stile in the wall for use by people using the Mass path through Clifford’s land.

Stations of the Cross are hung around the walls of the nave. Small brass plaques indicating the names of the donors were originally hung beneath them, but these plaques were removed during one of the renovation periods. The donors of the stations were Chris and Mrs. Cosgrave, William and Mrs. Walsh, Patrick and Mrs. Bailey, Dr. Coffey, Mrs. Dunne, Rathrone, Thadeus Magee, Mrs. Donegan, Drummond, Thomas Flynn, Peter and Jane Greville, John and Frances Thornton, Mrs. Slevin, Lizzie Barrington, James and Mrs. Boggan and Mrs. O’Grady. Another plaque that was once in the church, is now in storage there and is engraved:

Pray for the deceased Husband and Relatives of Mrs. John Monahan, Johnstown Bridge, R.I.P.

In 1931, Alphonsus Johnson, a painter and decorator from Tullamore, decorated the interior and renovated the exterior of the church.[40] In that year a communion plate was either purchased or donated. It is inscribed Jordanstown 1931.

In 1932, a new belfry was built at a cost of £347. The old bell was taken from its wooden structure and erected in the new belfry by James Troy, contractor, Tullamore.[41] Johnny Moore (Kilmore, Enfield), Jimmy Flynn (an uncle of parish residents Thady, Jimmy and the late Tom) and Tom Murray, Ballinderrin (father of Sheila Fagan, Baconstown) were some of the local men who assisted him. A large part of the cost of the project was met by Julia O’Grady, Enfield, with money she received from her uncle, Fr. M. Ryan, together with her own personal subscription.[42] A plaque was erected in the church and was inscribed:

Pray for the Very Rev. R. M. Ryan, Mullingar, Miss Julia O’Grady, Enfield and the others to whose generosity is due the erection of the belfry in this church. A.D. 1932.

A fatal accident was avoided during the erection of the bell by the quick action of one of the workmen. Jimmy Flynn, whilst working on the roof of the church, lost his footing and slid down. He managed to catch hold of the gutter and hung on.

A fatal accident was avoided during the erection of the bell by the quick action of one of the workmen. Jimmy Flynn, whilst working on the roof of the church, lost his footing and slid down. He managed to catch hold of the gutter and hung on.

Tom Murray saw him and on his own, picked up a long ladder and placed it against the gutter. This ladder was all in one piece and was so heavy that it normally took at least five strong men to move it. Jimmy Flynn managed to climb down the ladder and was grateful that his life had been saved by Tom’s quick action.[43]

In 1940, Fr. Eugene Daly, P.P. installed a new boiler to heat the church but the difficulty of securing fuel during the Second World War led him to comment:

I almost wish to be shipped east of Suez because of my difficulty to use the boilers to heat the peoples and my churches, but hope springs eternal in the human breast and thanks to wood and turf, I don’t despair.[44]

In 1949, P. Meehan, Navan, painted and decorated the church, and a contribution of £50 from Enfield GAA made possible the erection of two new doors. Six plain-glass windows in the nave of the church were replaced in 1949, as a result of a contribution from Cynthia Kennedy, Rathcore House. They were installed to commemorate the memory of her father, Dr. Antonio Kennedy and her grandfather, P.J. Kennedy. They are stained glass medallions of the Sacred Heart of Mary, St. Anthony, St. Patrick and St. Thérèse of Lisieux and are placed within leaded glass backgrounds. The windows were most likely the work of Myles Kearney, Dublin.[45]

In 1953, the ESB brought power to Jordanstown Church. T.P. Groome wired it at a cost of £68-17s-6d. An electric fire and a small cooker were bought for the breakfast room and thus eliminated the problems associated with a smoking chimney in the vestry. The church was lit up amid great jubilation, for Christmas 1953.[46]

In February 1957, during a particularly bad storm, slates blew off the roof of the church and a front window broke. People attending the removal of the remains of Tom Tevlin, Rathrone, had to crouch low in order to avoid being hit by flying slates. Fearing that the roof would blow off if the wind got under it, two local men, Mickey Greville and Joe Duffy, Jordanstown, got a ladder and in the midst of the storm climbed up and boarded up the broken window.

During his time as parish priest from 1965 to 1971, Fr. Patrick F. Abbott, P.P. modernised the church to post-Vatican II standards, following the ending of the Vatican Council on December 8, 1965. Hugh and Sam Quinn, Rathcore, carried out the work. Part of the marble altar was placed in a freestanding position, the altar rails were moved closer to the altar in order to allow for more seating in the church, and the altar rail gates were removed. Statues of St. Joseph and the Child Jesus, and St. Michael the Archangel, which stood on the left and right of the altar respectively were removed, as was one of St. Patrick, which stood at the top of the steps to the gallery.

In 1965, an amplification system was installed. Fr. Abbott also carried out other renovations including the installation of oil-fired central heating to replace the coal and anthracite previously used to heat the church. In 1966, the area around the church was cleared, a new side entrance gateway was opened and the yard was gravelled. In 1978, the church was re-dashed and painted at a cost of £7,000.[47]

In the mid-1980s, Nuala Langley, Johnstown, presented a set of vestments in memory of her husband Sean and her parents E.J. and Jeanette Daly to Fr. Timothy Buckley, C.C. for use in Jordanstown Church. Marie Cosgrave, Newcastle, made the bainín vestments and they were then hand-embroidered by Nuala.

In 1985, the church was closed for public worship from July 21 until October 20 in order to carry out major renovations, which cost £43,000.[48] During this period, Mass was celebrated in St. Patrick’s Community Hall, Enfield. The church was dry-lined, new flooring and gas central heating were installed and one of the confessional boxes was removed. The contractor was Camillus Slevin, Rathmolyon. On November 17, 1985, the Auxiliary Bishop of Meath, Dr. Michael Smith attended a special re-opening ceremony in the church (see also Chapter 13: Jordanstown Church Choir and Organists).

In 1986, Bishop Smith began to establish a pattern of a bishop visiting Jordanstown Church on a regular basis. His first visit was on May 29, 1986 and thereafter every second year, for Confirmation ceremonies. These ceremonies were normally held in Kill Church and only on three previous occasions were they held in Jordanstown. These were on June 16, 1914 when Dr. Laurence Gaughran came, on April 27, 1936 when Dr. Thomas Mulvaney visited and on April 23, 1948 when Dr. John Kyne attended. [49]

Fr. T.P. Gavin carried out many improvements to the church during his period as curate in the parish. In 1989, he installed exterior lighting and in 1990, he had the sacristy in the church reordered. As part of this work, Michael Heffernan, builder, Rathmolyon, fitted new vestment presses. In that year also, a new amplification system was installed at a cost of £1,200. In 1991, a car park was developed at the church and the surplus topsoil – sixty-five dump truck loads – was brought to Baconstown National School and used to improve the school playground and pitch. In 1993, new lighting was installed on the gallery, the church was painted and the sanctuary lamp was moved from its central position in front of the altar to the side of the sanctuary. Handrails were fitted near the front doors to facilitate people entering and leaving the church. In 1995, a new church organ costing £4,500 was purchased from Jeffers & Co., Bandon, Co. Cork. Land for use by the parish was purchased from Joe (Basie) Greville.

In March 1997, Our Lady Queen of Peace Prayer Group was formed in order to prepare for Jubilee 2000. Prayer meetings were held in Jordanstown Church in March and August of each year, up to 1999. The devotions included Mass, exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, Rosary and chaplet of Divine Mercy and ended with the blessing of the relic of Sr. Faustina, who was canonised on April 30, 2000. Sr. Assumpta McElduff brought the relic from the Sisters of Mercy Convent, Trim, and blessed the people. Since March 2000, the meeting has continued in the form of a Mass of healing.

In order to mark Jubilee 2000, an oak tree was planted near the rear of the church, after a prayer service on Millennium Eve, 1999.

Shortly after his appointment to the parish in October 1999, Fr. Michael Whittaker, C.C. began investigating the prospect of repairing and restoring the stained glass windows, which were in poor condition. Much of the artwork was faded to a degree that it was becoming difficult to distinguish the features on the faces of the figures and the designs on the clothing. The windows were buckling due to heat from the sun and also from the weight of each section of glass and lead resting directly upon the section beneath. The Abbey Stained Glass Studios, Kilmainham, Dublin, were contracted to carry out the work, which involved taking out the windows, removing the lead, cleaning the antique glass and carrying out repairs. The studio’s senior artist, Kevin Kelly carried out much of the artwork restoration.[50] The windows were re-leaded and replaced in the church. The cost of restoring the windows, providing exterior stormglazing and carrying out repair work around the windows cost €113,959 (£89,750) and the work was completed in January 2001.

Between January and April 2002, painting contractor Alo Kelly, Trim, painted the interior of the church and sanded and varnished the floor.[51] In March 2002, a large picture of the Divine Mercy and an electronic candelabra dedicated to the Divine Mercy were placed in the church. In November and December 2002, the floorboards on the gallery were lifted up and the boards and joists treated. Michael Heffernan, Rathmolyon, carried out the work. New carpet was laid and new seats were fitted on the gallery.[52] The crib figures were repaired and restored in time for Christmas 2003[53]. In February 2004, a new sound system, which included an outside speaker for large gatherings, was installed.[54]

Fr. Whittaker had earlier embarked on a major fund-raising campaign and in the period from April 2000 to March 2004, €213,481 had been collected.[55] This funding was achieved through monthly envelope collections, donations, golf classics and table quizzes. In February 2004, plans were put in place to obtain additional funding through a tax relief scheme, whereby the parish, as an eligible charity, could reclaim tax paid by parishioners on donations of €250 or more per annum to the parish. The scheme had come into effect in 2001 and appropriate forms were submitted to the Revenue Commission in respect of the three years from 2001 to 2003.[56]

During late 2003/early2004, 1.3 acres of land adjoining the graveyard, was purchased for €35,000 from Progressive Genetics Co-operative Society Ltd. and in February 2004, Meath County Council granted planning permission to develop this land as a new graveyard. On Sunday, February 20, 2004, a new Baptismal Font made by Paul Hanley (Rathcore) was blessed at 11.00 a.m. Mass. The stainless steel bowl from the old font had been fitted in the new one.

Jordanstown Church is, at present, in an excellent state of repair. The care that has been taken of the church, which is at least one hundred and seventy years old, is due to the dedication of the clergy and the generosity of the parishioners. That care, which has been evident for centuries, continues up to the present day.

1 Ordnance Survey Field Name Books of the Co. of Meath, 1835-1836, Parish of Rathcore, Vol. XXXVI, No.121, p. 116.

2 Rev. John O’Hanlon, M.R.I.A., Lives of the Irish Saints, James Duffy and Sons, Dublin, pp. 475, 476.

[3] James Kenney, Ph.D., The Sources for the Early History of Ireland, Columbia University Press, New York, 1929, p. 180.

[4] Philip O’Connell, Loughan and Dulane in Ríocht na Midhe, 1958, Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 18.

[5] Beryl F.E. Moore M.B., Rathcore, County Library, Navan, 1972, pp. 2, 11, 12.

[6] Rev. Anthony Cogan, The Diocese of Meath, Ancient and Modern, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1992, Vol. II, p. 200.

[7] ibid.

[8] ibid., Vol. III, pp. 25, 26.

[9] ibid., Vol. II, p. 207.

[10] Rev. John Brady, A Short History of the Parishes of the Diocese of Meath 1867-1937, Vol. 1, p. 188.

[11] ibid., Vol. 1, p. 189.

[12] Meath Chronicle, March 28, 1908, p. 1.

[13] The late Mickey Cooke, Rathcore.

[14] Freeman’s Journal, p. 2. Viewed on microfilm in the National Library of Ireland, Dublin.

[15] The Central Bank of Ireland, Dame Street, Dublin.

[16] Mary Hayden, George Moonan, A Short History of the Irish People from 1603 to Modern Times, Educational Company of Ireland, 1960, p. 441.

[17] Brian Griffin, Some intriguing parson, who wishes to attract attention in Ríocht na Midhe, 2000, Vol. XI, p. 110.

[18] James Lydon, The Making of Ireland, Routledge, London and New York, 1998, pp. 288, 289.

[19] Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, 1837, Vol. 2, p. 493.

[20] Brady, op. cit., Vol. 1, p. 189.

[21] Chronicon of Enfield Parish.

[22] Drogheda Independent, October 4, 1902, Meath Chronicle, April 20, 1935, p. 12 and Leinster Leader, August 12, 1893, p. 5.

[23] Leinster Leader, July 15, 1893, p. 5, viewed on microfilm in the National Library of Ireland, Dublin.

[24] Leinster Leader, August 12, 1893, p. 5, viewed on microfilm in the National Library of Ireland, Dublin.

[25] ibid., p. 7.

[26] Michael J.F. McCarthy, Priests and People in Ireland, Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd., 1903, p. 134.

[27] The Meath Chronicle, January 5, 1907 and Patricia Reynolds (Melia), Dublin.

[28] Meath Chronicle, March 28, 1908, p. 1.

[29] ibid.

[30] The Irish Builder and Engineer, June 1, 1907, Vol. XLIX, No. 11, p. 393

[31]The Irish Builder and Engineer, April 4, 1908, Vol. 50, No. 7, p. 213.

[32]The Meath Chronicle, March 28, 1908, p. 1.

[33] The Meath Chronicle, March 28, 1908 and Brady, op cit., Vol. 1, p. 189.

[34] Ken Ryan, The Abbey Stained Glass Studios, 18 Old Kilmainham, Kilmainham, Dublin.

[35] ibid.

[36] The Meath Chronicle, March 28, 1908, p. 1.

[37] ibid.

[38] The Abbey Stained Glass Studios, op. cit.

[39] The Registry Of Deeds, Chancery St., Dublin, Folio No. 3778 and Folio No. 5050, Instrument Nos. 129071 and 1742/10/59.

[40] Chronicon of Enfield Parish.

[41] ibid.

[42] ibid.

[43] Michael Reynolds, Dublin and formerly Rathrone, Enfield.

[44] Chronicon of Enfield Parish.

[45] Chronicon of Enfield Parish and The Abbey Stained Glass Studios, op. cit.

[46] Chronicon of Enfield Parish.

[47] ibid.

[48] Olive C. Curran, History of the Diocese of Meath 1860-1993, Criterion Press, 1995, Vol. 2, p. 455.

[49] Parish Confirmation Register.

[50] The Abbey Stained Glass Studios, op. cit.

[51] Parish Information Leaflet: the painting of the interior of the church cost in the region of €21,000

[52] Parish Bulletin, November 24, 2002 and Parish Information Leaflet. The cost of refurbishment of the gallery was €10,900 – new seats cost €6,900 and repairs to gallery floor and carpet cost €4,000.

[53] Parish Information Leaflet: the cost was €2,500 and included repairs to some of the church brass.

[54] Parish Bulletin, February 22, 2004 and Parish Information Leaflet, March 23, 2004. The cost was €3,500.

[55] Parish Bulletin, March 22, 2002, Parish Information Leaflet, March 22, 2003 and Parish Information Leaflet, March 23, 2004. From April to March 2000, €65,074 was collected; 2001 – €57,799; 2002 – €42,500; 2003 – €48,108.

[56] Parish Bulletin November 21, 2004: In November 2004, €21,560 was received from the Revenue Commission.

Church of St. Michael the Archangel, Rathmolyon

On May 28, 1945, Most Rev. Dr. John D’Alton, Bishop of Meath, on his visit to the parish of Kill and Jordanstown for the administration of the Sacrament of Confirmation in Kill Chapel, said that in the future a new church would be needed. He stated that whilst the present church was still in a good state of repair, it was not one on which money should be spent. He recommended that a fund be started for a new church and he personally opened the account with a contribution of £100.

The parish priest, Fr. Eugene Daly put the proposal of a new church to the parishioners in both Kill and Jordanstown and received an enthusiastic response. It was agreed that a five-year collection plan be adopted. Many people gave an immediate subscription and others adopted a five-year instalment plan. By the time a Confirmation ceremony was again held in the parish on April 23, 1948, a sum of £5,800 had been subscribed.

The fund raising efforts, which included wheel of fortune, sales of work and concerts, continued for many years. Fr. Thomas F. Gillooly, C.C. and Fr. Patrick Dillon, P.P. were to the forefront of the campaigns and Fr. Joseph Casey, P.P. bequeathed personal money and the proceeds from the sale of his possessions after his death, to the church building fund. Other priests were involved in running bingo and dances to raise funds. A special church envelope collection put in place in the early 1960s was a great success and brought in about £5,000 annually.

Phil Fitzsimons who died on March 14, 1962, bequeathed his house and garden at Cherryvalley, to St. Finian’s Trust, with the intention that the area be used as the site for the new church. The property remained in Church hands until October 21, 1971 when it was sold to Thomas and Olive Doherty. A site closer to the centre of greater population in Rathmolyon village was preferred to the more rural area near Kill. In 1966, Elizabeth Sweeny and her daughter, Ann Sweeny, Cherryvalley, donated a site on the main Rathmolyon-Ballivor road, for the building of a church, a parochial house and for the development of a car park. Fr. Gillooly had previously used the field on many occasions for the holding of a fete to raise parish funds. On April 29, 1966, when Most Rev. Dr. John Kyne, Bishop of Meath visited the parish for the Sacrament of Confirmation, Fr. Patrick F. Abbott, P.P. took him to see the site.

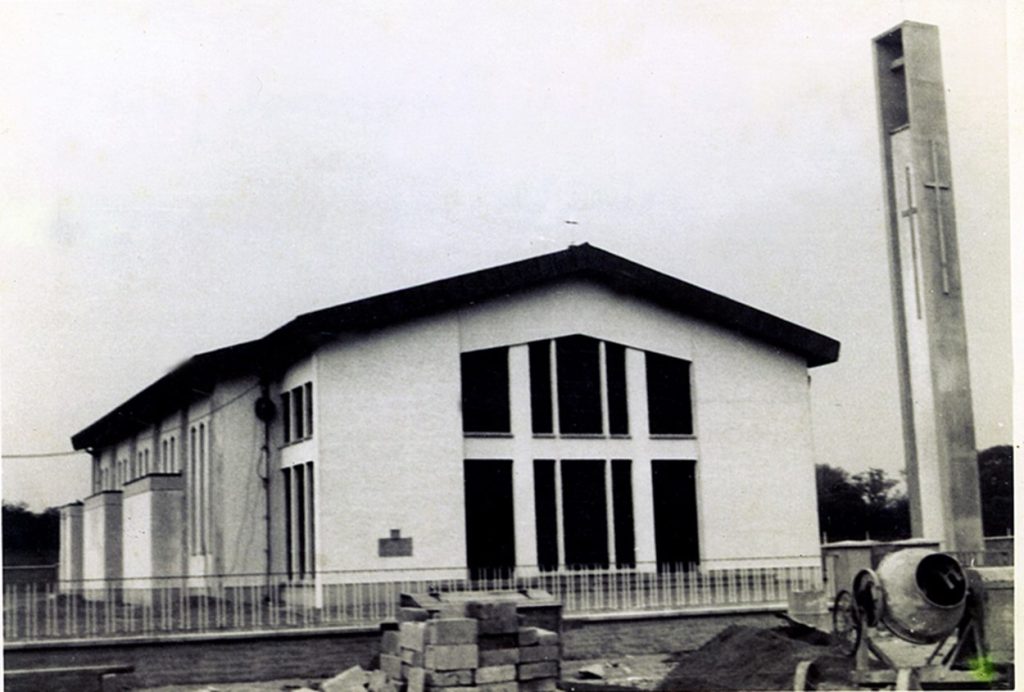

The architect engaged was Simon Leonard F.R.I.A.I. of Messrs. W.H. Byrne and Son, Dublin. The quantity surveyors were Leonard and Williams, Dublin and the building contractors were Messrs. Cormac Murray (Building) Ltd., Ardsallagh, Navan. Work began on September 4, 1966, and on October 4, the first bag of cement was used.

On July 9, 1967, Monsignor Laurence Lenehan, Tullamore, Vicar Capitular, assisted by Fr. Abbott blessed the site of the altar and blessed and laid the foundation stone. The inscription on the stone reads:

D.O.M

Foundation Stone

St. Michaels Church Rathmolyon

Blessed and laid by Right Rev.

Mgr. Laurence Lenehan Vic. Cap.

9th July 1967

assisted by V. Rev. P. F. Abbott P.P.

Patsy Farrell, Rathmolyon, presented the trowel used for the laying of the foundation stone. A glass container placed in a hollow in the stone contained medals, a relic of Blessed Oliver Plunkett, a set of 1967 Irish coins and a brief history of the parish and of the building of the church.

On completion of the building work, the sacred vessels, holy water fonts, baptismal font and some statues from the old chapel in Kill were brought to the new church. On Sunday, July 14, 1968, Most Rev. Dr. John McCormack, Bishop of Meath came to Rathmolyon to bless and dedicate the new church to St. Michael the Archangel. On arrival, Fr. Abbott and Commandant C. Stapleton, D Company, 7th Battalion, FCA escorted him to the church grounds, where he inspected a guard of honour from D Company under Lieutenant Patrick Clarke, Longwood. He then solemnly blessed the new building. This was Dr. McCormack’s first such function since his consecration the previous March. Fr. Gillooly, a former curate and Fr. P.J. Regan, a native of the parish, assisted in the dedication ceremony. Fr. Joseph Abbott, Administrator, Navan and Fr. Michael Deegan, a former curate led the chanting of the Liturgy of the Saints. Along with seven priests, the bishop concelebrated Solemn High Mass. Servers included Paddy Forde (Kill) and John Brady (Riverdale, Rathmolyon), who also carried the cross at the head of the entrance procession. The priests included former curates, Fr. Gillooly, Fr. Deegan, Fr. Aidan Farrell and Fr. Edward Rispin, and priests native to the parish, Fr. Regan, Fr. Leonard Moran and Fr. Sean Slattery. Fr. Colm Murtagh, parish curate acted as master of ceremonies and Fr. Regan delivered the sermon. Following the ceremony, the Legion of Mary served refreshments in Rathmolyon Hall, which had been placed at the disposal of Fr. Abbott by the Church of Ireland community.

The total cost of the church was between £60,000 and £70,000 but resulted in no serious debt, as parish funds that had been collected for over twenty years, almost covered the cost.

The church may be described as a long, low-pitched building, one hundred and seventeen feet long, sixty-seven feet wide and twenty-seven feet high. The exterior walls are finished in white dashing and the copper-covered roof is surmounted at the front with a slender golden cross. The almost square-shaped nave is a break from the traditional cruciform or aisle churches. The layout of the large sanctuary is in keeping with modern liturgical requirements and this is the only church in the parish to be customarily built to meet post-Vatican II standards. The ceiling is of an unusual concertina or saw-tooth shaped design and is treated with a special spray material to give the best possible acoustical properties to the nave.

To the front of the building are the two main entrance porches and a baptistery, with a choir gallery overhead. In addition, there is a side porch and to the rear of the church are a priests’ sacristy, servers’ sacristy, toilets and a storeroom. The two recessed confessionals are confined to one side of the church and are of polished hardwood, with slender glazed door panels.

The sanctuary windows, which rise from floor to ceiling, highlight the altar furnishings.

A large stained glass window depicting the Godhead and the saving of the world through Baptism and the Holy Spirit dominates the main entrance. The sidewalls incorporate panels of stained glass windows.

The inclusion in the design of three rows of seating means that no person is more than sixty feet from the sanctuary. The rows are divided by two aisles that run the entire length of the church and access to the seats is also provided by two side aisles. The seating capacity of six hundred nearly doubles that of the old chapel at Kill.

On September 20, 1968, Dr. McCormack revisited the church to consecrate the altar and offer Mass for the deceased members of the parish. Stations of the Cross plaques were blessed and erected but the figures for them did not arrive from Italy until three months later, when on Christmas Eve, local men Patrick Broderick and James Dunne placed them in position. The old bell from Kill Chapel had been erected in a specially built tower in the church grounds but due to problems with its audibility, an electric carillon was installed in July 1978.

Today, the church is in excellent repair. Its presence is due to the foresight of the bishop of the diocese and the clergy of the parish, and to the generosity of the people. It has earned its place in their hearts and their care of it is testimony to this.

Sources:

The Meath Chronicle, July 13, 1968.

The Irish Independent, Monday, July 15, 1968.

The Irish Press, Monday, July 15, 1968.

The Drogheda Independent, July 19, 1968, p. 1.

The Meath Chronicle, Saturday, July 20, 1968, p. 1.

The Meath Chronicle, Saturday, July 27, 1968, p. 12.

Chronicon of Enfield Parish.

Conversations with local people, whose names are included under Acknowledgement to contributors.

Graveyard History

Graveyards are very important places, both as a respectful resting place for our loved ones and as part of our valuable heritage.

A survey was carried out on graveyards in the Enfield Common Bond Area by members of Baconstown Heritage Group. Read More >>